Moscow TV!

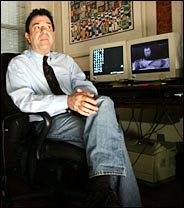

KEN SCHAFFER doesn’t like blind spots. Never has.

Mr. Schaffer received a Heathkit radio for his 10th birthday. Inspired by the signals from satellites chirping from space, he soon became a world-class ham-radio operator, adept at Morse code.

“It was compelling that I could just go beep-beep-beep, the smallest possible muscle group movement, and I could send a signal that goes to China,” he recalled recently. “I would never answer people from New Jersey or Long Island or anything. I wanted Mongolia.”

Years later, after detouring to invent the wireless microphone, travel with the Rolling Stones and make guitars for John Lennon, Mr. Schaffer installed a satellite dish atop his Midtown Manhattan apartment building and was soon pulling in broadcasts from the Soviet Union.

“I wasn’t interested in HBO and free Showtime,” he said. “It was not interesting to me. I was watching Russian feeds from Moscow to Cuba – and what they used to do after they finished the feed is, the Russians would send porno to Havana, or American films. And this was before Gorbachev and all that kind of stuff.”

Inspired by the potential of satellites to open up communication, Mr. Schaffer soon built a satellite telephone operation connecting the Soviet Union with the West, a venture that he sold for millions in 1995.

Now, Mr. Schaffer is trying to abolish yet another blind spot. In short, he has devised a way to make home TV reception portable – with high-quality pictures to be watched, and channels to be changed, from anywhere in the world that the Internet can reach.

So far, he has put his PC-based innovation into the hands of a few dozen others willing to pay several thousand dollars. But he aims to reduce the price to less than $1,000 within a year.

“Kenny is not your everyday eccentric,” said Jonathan Sanders, a consultant to CBS News in Moscow who has known Mr. Schaffer for more than 20 years. “Kenny is an explosion of genius wrapped in a very unconventional package that is bursting with energy. This is somebody who is doing the kinds of things that you read about at one time only in science fiction, things that no one else thinks are possible but that he is able to pull off.”

So much was clear one Tuesday afternoon last month.

“So this is like the Russian version of a cross between ‘E.R.’ and ‘Law and Order,’ ” Mr. Schaffer said. He was sitting at a desk in the apartment next to the Plaza Hotel. Spread before him were computer monitors. On one was a live cable television feed from the apartment he keeps in Moscow. On another, a live London feed was displaying a somewhat risqué commercial for a British cellphone carrier.

The quality of the full-screen images bore no resemblance to what the rest of the world thinks of as streaming Internet video. It was not quite real television, but there was very little of the pixilation and none of the incessant stuttering familiar to anyone who has watched live video over the Internet. The main character appeared on the Russian medical drama, and Mr. Schaffer jerked back a bit. “Arrgh! That’s my ex-wife!” he said, pointing at the actress, Alla Kliouka.

Mr. Schaffer popped out of full-screen mode, clicked, and switched the channel to MTV Russia.

In fact, Mr. Schaffer was controlling a dedicated computer terminal back in Moscow that was simultaneously connected to his Moscow cable box and a D.S.L. data line. The terminal, which Mr. Schaffer calls TV2Me, uses a small infrared emitter to tell the cable box which channel to display. Inside TV2Me are special computer cards that allow the unit to send high-quality video over a routine broadband data connection.

In his bedroom is a huge Sony plasma flat-panel television. He puts up the same Moscow channels that were on the laptop in the living room. Even on the big screen, the images are fluid and clear.

It was an impressive demonstration, but a somewhat ironic one as well. Sony, it turns out, has just developed a similar product, called LocationFree TV. Both TV2Me and LocationFree TV allow a user to view their home television from anywhere in the world that has a high-speed Internet link, even a Wi-Fi connection outdoors. The Sony unit is cheaper. The home base station of the Sony unit is smaller. Sony’s user interface is slicker. But for all that, Mr. Schaffer’s unit transmits a clearer picture over the Internet.

So how did he do it? And why?

Mr. Schaffer has always been a TV guy, and a stickler for picture quality.

“We had one of the first televisions in the Bronx,” he recalled. “I remember vividly standing in the living room in front of this round-tube TV thing, this huge console, watching the first transmission of ‘The Huntley-Brinkley Report’ in color and screaming to my mother, ‘I can see the colors, I can see the colors!’ “

In 1975, Mr. Schaffer bought one of the first big-screen projection televisions in New York City, an 84-inch monster made by Advent. He had been working as a rock music technician and publicist, and Mr. Schaffer said that Ron Wood and Keith Richards of the Rolling Stones would sometimes come over to review concert tapes on the big screen.

Also that year, Mr. Schaffer was living with the band’s tour director when he noticed that whenever Mick Jagger would switch to a wireless microphone, the sound quality collapsed. “Sometimes the police radio would bleed through and it would be, ‘There’s a body floating in the East River’ or something, in the middle of a show,” Mr. Schaffer said.

Mr. Schaffer set about inventing a wireless microphone that would actually work well and came up with a system that lent itself to a wireless guitar as well. His customers ended up including not only the Stones and John Lennon, but also Pink Floyd, Peter Frampton, Fleetwood Mac and others.

Two decades later, after Mr. Schaffer’s venture into satellite phone service – an endeavor that brought him a 14,000-word profile in The New Yorker – he started playing around with Internet and Web systems. He took a look at what was being called Web video and was not impressed. “I saw what was presented as Internet TV on Yahoo,” he recalled. “It was the equivalent of the microphone Mick Jagger was using when I said I could do better than that. It’s a one-to-one equivalent.”

All the while, Mr. Schaffer was shuttling between New York and Moscow, where he estimates that he has spent a total of perhaps four years out of the last 20. Russian television improved through the 1990’s, but he still could not get what he wanted. “I missed ‘Seinfeld,’ ” he said. “I wanted to watch Ted Koppel and ‘The Sopranos’ and ‘Saturday Night Live.’ “

He started working on TV2Me in earnest in 2001, and he has ended up using the same basic compression technology that Sony is using, called MPEG-4. But while Sony is essentially using standard MPEG-4 by itself, Mr. Schaffer and his team of Turkish and Russian programmers have developed circuitry that allows the MPEG-4 encoder to operate more efficiently and to generate a better picture.

“All of his projects have to do with connecting people and also something beyond the norm,” said Robert E. Bishop, an old friend of Mr. Schaffer’s and a managing partner of Tekseed L.L.C., which is developing a separate video system for security applications. “For him, it has to be something that is advancing technology. I think he was trying to take existing hardware and put it together in a way that really improved the science of moving video from Point A to Point B.”

The engineering has always come naturally to Mr. Schaffer. The business side is another matter. He built a big business out of the wireless music technology in the 1970’s, but never patented his inventions. He sold his satellite company for millions to a company now part of the military contractor Lockheed Martin, but he lost much of the proceeds in bad investments during the 1990’s technology boom.

This time, Mr. Schaffer is trying to play by the book, a change he attributes to an enhanced sense of responsibility after having a child with Ms. Kliouka in 1995. He has patents pending. He has lawyers.

For now, he has sold only a few dozen TV2Me units, at prices ranging from $4,800 to more than $6,000. Many of his clients so far are well-heeled sports fanatics who simply must get their games when on the road. One client is a University of Oklahoma football fan. Another, a British rock star, needs his soccer.

Within a year, Mr. Schaffer hopes to reduce the price to less than $1,000. Right now, the product is based on a high-powered Pentium 4 PC running Windows, but by building special chips that can focus on only the tasks required for TV2Me, such a product can be made lighter, smaller and cheaper. The use of such chips is a big reason Sony’s product is so much less expensive than TV2Me.

In fact, Mr. Schaffer says he may end up selling his entire technology. “I’d like to see this go to a company,” he said, indicating that he already has buyers in mind. Mr. Schaffer is keenly aware of the copyright and other legal issues potentially posed by his technology, which does, after all, retransmit cable or satellite television signals over the Internet. He insists that each customer put his systems only to personal use.

“I want to stay absolutely within the law,” he said. “On a personal level, I paid for this cable.” What separates him from other cable subscribers, he said, is simply that “I have a long extension cord.”

But he said he had turned down overseas sports bar owners who want to show American football to attract expatriate customers. And he has built roadblocks into his system meant to prevent users from sharing their video feeds with others.

For now, he says he has not heard from any unhappy networks or satellite or cable television operators. A spokesman for Time Warner Cable, the main cable carrier in Manhattan, declined to comment on either TV2Me or Sony’s LocationFree TV.

But just as television companies at first largely ignored digital video recorders like TiVo, only to wake up later, devices like TV2Me may offer new challenges and opportunities to the entertainment industry sooner than expected. TiVo users sometimes refer to their practice as “time shifting,” that is, watching television on their own time.

Mr. Schaffer refers to the use of his product as “space shifting,” as in watching television in one’s own space. (His Web site is www .spaceshift.net.)

More broadly, Mr. Schaffer hopes that his life of eliminating blind spots has done just a bit to make humanity safer. “I think the more that you eliminate borders between countries, people, ideas, the more likely it is that we’re going to make it another couple of hundred years,” he said. “That’s what my motivation is.”

By Seth Schiesel

The New York Times Original article (requires registration) here