How Boris Grebenshikov became the first Soviet rocker to have an album released in the West

It’s 9 o’clock in the morning – virtually dawn by New York standards – and Ken Schaffer doesn’t want to talk. “Just listen,” he says, running over to the bank of tape decks by the wall.

He flips a cassette into the machine and suddenly, 21 floors above mid-town Manhattan, the room fills with the sounds of bass guitar, keyboards and a voice that’s a cross between that of John Lennon and Roxie Music’s Brian Ferry. Schaffer puts his feet up on his desk and smiles His hands make little drumming motions in the air. When the song ends, he says: “The truth is, I was just going on faith.”

Faith has served Schaffer well. Overcoming a variety of technical and legal challenges, Schaffer, who is 39, developed a system to bring live Soviet television to the United States in the early 1980s. In 1987, while ABC was broadcasting its “Amerika” mini-series, a fictional account of a Soviet takeover of the United States, he and his partner, Marina Albee, 27, were providing cable’s fledgling Discovery Channel with 66 hours of real Russian TV. The point, as Schaffer puts it, was to “let the people of one country look into the living room of the other.”

Today, Schaffer and Albee are about to introduce Americans to the 34 year old Soviet underground rock superstar Boris Grebenshikov, the voice on Schaffer’s cassette deck.

Even though Grebenshikov and his band, Aquarium, have been among the Soviet Union’s most popular musicians for the last 10 years, Grebenshikov has had to work full time in a Leningrad factory to support himself and his wife in a 6th floor walkup they share with two other couples Until recently, the police broke up his concerts, and the Soviet press called his work the musical equivalent of alcoholism.

These days, though, his fortes are on the upswing. Grebenshikov is commuting from Leningrad to New York and Los Angeles, dining with the likes of David Bowie, Debbie Harry and Lou Reed and fielding calls for interviews from Rolling Stone, Billboard, the New York Times and People

Last April, when he signed a six-figure recording contract with CBS Records, Grebenshikov became the first Soviet musician not approved by the government ever allowed to make an album in the West. He has spent most of the last few months in the studio, singing (in English and Russian) with such Western luminaries as Dave Stewart and Annie Lenox of Eurythmics and Chrissie Hynde of the Pretenders. And in March, as part of an agreement between CBS Records and its Soviet counterpart, the state owned Melodiya label, his will be the first album released simultaneously in both East and West.

How did Boris Grebenshikov, a man who until recently couldn’t legally perform in public, come to be allowed to make a record in the United States?

The story begins with Schaffer. In 1981 he was sitting in his Manhattan penthouse recovering from 15 years of rock ‘n’ roll. He had been a publicist for Jimi Hendrix, Alice Cooper and Lenny Bruce. He had invented the first workable wireless microphone and the cordless electric guitar (both of which he’d neglected to patent), While strong on ideas, Schaffer is clearly weak on the business details. He’d made a fortune as a press agent, lost it and made another on the guitar and microphone. His motivation? As he explains in his own deadpan, “I was bored; I needed a new ‘thing’.

Just for fun, he went out and built a satellite dish. He hoped to intercept cable-TV signals, but he soon discovered that his roof was too low and that the buildings of midtown Manhattan blocked virtually all satellite transmissions. The only satellite broadcasting came from directly overhead and it was Russian. “I didn’t care if it was only the test pattern,” Schaffer says. “I just needed some satellite signal in the house”

One night, while the most of Manhattan tuned in the networks and American cable, Schaffer pointed his dish straight up into the sky. “And the image I saw,” he says, “even though the program was in black and white, with no sound, this creaking opening of the window hypnotized me.”

Schaffer was hooked, but he had a problem. Although Western satellites hover over a single point on the Earth’s surface (making their signals easy to follow), the Soviet Molniya, which he had picked up, was one of four satellites moving in a north-south orbit around the planet To track the signal, he had to move his dish by hand every three minutes. Moreover, he had to figure out a way to turn the silent black & white image he was receiving into a full color broadcast, complete with sound.

It took him two years, but by the end of 1983 he had learned how to keep his dish focused on the Soviet signal and had designed a decoder to turn that signal into television. In the process, Schaffer discovered that Soviet television “may be boring, it may not be good television, but watching it is an eye opener. I started seeing things that should not have been profound but in fact were. things like, they wear clothes, and they breathe.”

ln the meantime Schaffer tried to sell his invention to universities. He figured that as soon as professors heard that their students could “watch CBS on Channel 2 and Moscow on Channel 3,’ they’d buy. “But,” he says, “I went to Yale and Harvard’ and, you know, they said, ‘We don’t even watch American TV.'”

Enter Jonathan Sanders, then assistant director of the Harriman Institute for Soviet Studies at Columbia University. Sanders had been looking for someone to build him just the kind of system Schaffer bad designed. (He had already talked with more than 40 satellite ‘experts’ most of whom made him think that “in their previous incarnations they’d sold snake oil” When he met Schaffer, though, he decided to take a chance. “I thought it would be fun,” lie explains, “to work with someone as crazy and unregimented as Mr. Schaffer. And I thought he could do it”

Columbia wasn’t so sure. “Columbia,” says Schaffer, “had the proposal scrutinized by RCA, Intelsat, Comsat, and they all said it wouldn’t work.” Fortunately, Sanders was able to find a private donor willing to put up the $38,000 needed to get the system installed, and at 4 o’clock one afternoon in August, 1984, Columbia became the first place in the country able to eavesdrop on live Soviet television.

One of those students was Marina Albee. After graduating from the University of Vermont, she had taken a summer course in Russian. She had hoped to use her language skills at the United Nations, but after leading a tour to the Soviet Union, she knew she needed to learn more about the country itself. “Before I went over there,’ she explains, “I knew nothing about the place. All my images of it were from our media, images that tended to be black and white.” Albee decided to attend Columbia because, as she saw it, it was the only school offering an antidote to those images.

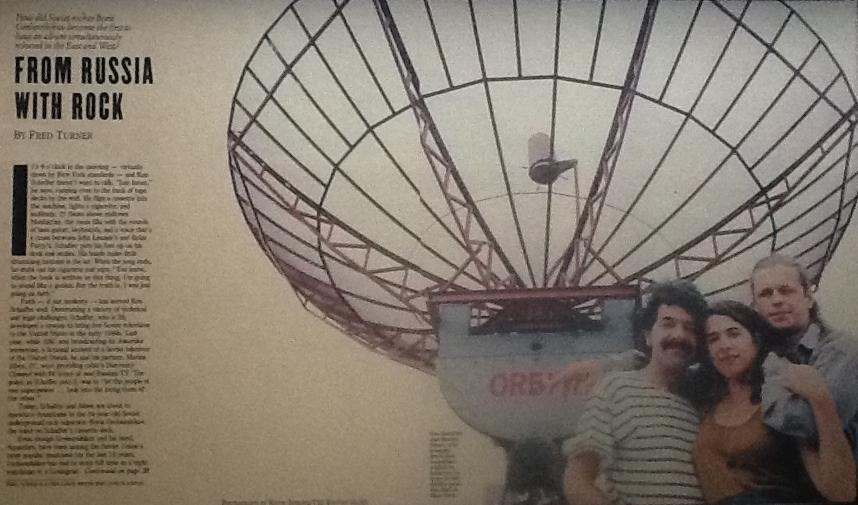

One day in the middle of her first semester, Albee met Schaffer. He sought her advice on a variety of issues, and two months later he offered her a job as vice president of Orbita Technologies, the company he had created to market his satellite receiving system. Albee accepted, not only because the job entailed working directly with the Soviets but because it meant working with Schaffer. “I was persuaded by his unwillingness to see the downside of things. He’s like an idiot savant. He says this can happen, that can happen, and all the experts in the world say never in a million years.”

Despite his success at Columbia, other universities declined to buy the Orbita system because the programming it brought down laid no clear copyright status. because the Soviets, had not given anyone permission to use their satellite signals, those who did so were seen as pirates.

In December, 1985, Schaffer joined her for a trip to Moscow. They connected with Victor Khrolenko, an old friend of Jonathan Sanders and, at that time, a freelance guide to Soviet officialdom. Khrolenko took them to Gosteleradio (the agency responsible for television and radio). According to Schaffer, “rather than putting us on a bus to Siberia, they said, ‘How can we help?” Six months later Orbita received the exclusive Schaffer was offering the Discovery Channel rights to broadcast internal Soviet television 66 hours of live Soviet internal television to in the United States for educational purposes.

Over the next two years, Schaffer and Albee sold a half a dozen of their dishes to universities around the country, for $50,000 each. At the same time, Mikhail Gorbachev’s policies of glasnost and perestroika began to take root in the Soviet Union. Albee and Schaffer found themselves besieged by Americans wanting help with their projects in Russia, and they realized that with Gorbachev in the Soviet Union laid become, in Schaffer’s words, ‘virgin commercial territory.’

Schaffer won’t talk about how much money he has made from the Soviet ventures. As first, he insists, he was amply intrigued by the technical challenge of bringing down Soviet TV signals from a satellite. If his intention turned a profit, so much the better, but, says Schaffer, “the money was, and is, beside the point, The invention changed the inventor, and I threw away my soldering gun.”

Although Schaffer may have grown increasingly interested in cross cultural change, others were intended on profiting from the recent improvement in superpower relations, To help them, Schaffer and Albee recruited Khrolenko and his wife, Cynthia Rosenberger, and formed Belka International. Belka (named for the first Soviet spacedog to come back to Earth alive) began to act as a liaison for American television networks, publishers and manufacturers engaged in joint ventures with the Soviets. Belka’s clients included Collins Publishing (producers of the book “A Day in the Life of the Soviet Union”) and Life Magazine. Belka also helped to produce space bridges (by satellite communications) between the U.S. Congress and the Supreme Soviet and helen journalists in Boston and Moscow.

Yet even though the Soviet Union seemed to be opening up to Belka’s clients, the overall climate between the two superpowers remained fairly cool. In February of 1987, for example, Schaffer and Albee were meeting with officials at Gosteleradio in Moscow when the Soviets received a telex from ABC. The telex announced that in two weeks ABC would broadcast its “Amerika” mini-series.

Schaffer frowns as he remembers the meeting “The mood of the Soviets just plummeted,” he says. “They were sincerely hurt They were very upset that media time could be used to create a negative image with no positive.”

When he returned to New York, Schaffer called John Hendricks, chief executive officer and founder of the Discovery Channel and introducing himself by saying, “My name’s Kenny Schaffer. You don’t know me, but would you consider pre-empting everything you have next week?” Schaffer was offering the fledgling Discovery Channel 66 hours of live Soviet internal television before, during and after ABC’s “Amerika.” Except for the Soviet evening news, all programs would be shown in Russian, with only occasional contextual translations.

Hendricks was skeptical but intrigued. The next day he and Discovery Channel President Ruth Otte flew to New York from their headquarters in Landover, MD. When they saw the Orbita system at Columbia, Otte says, “We were moved by how many of our stereotypes about the

Soviet Union were smashed by watching this television. There wasn’t time to do any research. There wasn’t time to poll any of our viewers. We simply had to go on our own gut judgment”

Hendricks and Otte gave the go ahead. The show was to be called “Russia – Live from the Inside” and was to premier on Sunday, Feb. 15. On Friday afternoon, two days before the program was to air, they received a telex from the Federal Communications Commission telling them that what they were about to do was illegal. The telex explained that by taking programming directly from a Soviet satellite rather than from a satellite owned by the Western bloc network, Orbita would be violating American agreements with Intelsat partner nations. The FCC threatened to fine all parties involved.

Schaffer was furious. He and his attorneys maintained (and still believe) that not only was their project legal but that the FCC had no jurisdiction whatsoever.

With only 48 hours to go, though, Schaffer had no time to argue the point He called the United States Information Agency in the hope that it would intervene on Orbita’s behalf, but it would not As a result, he and the Discovery channel were forced to route their transmissions through an Intelsat satellite, an extremely expensive procedure. Because of the cost, only half of the programming could be shown live. The rest consisted of tapes made by the Soviets of material shown the previous week.

Even so, “Russia: Live from the Inside” marked the first time the American public had ever had the chance to see Soviet television as Soviet citizens see it. The program earned a Golden Ace Award from the National Academy of Cable Programming and, according to Otte, doubled the Discovery Channel’s audience.

If the broadcast was so successful, why had the federal government tried to stop it?

By Fred Turner